Honey bee colonies are perennial in nature. They undergo an annual cycle based around the seasons however they persist in the hive year-on-year. This differs from similar creatures such as bumble bees and common wasps where the colony – in effect – collapses at the end of the season. Bumble bees and wasps spend their season building up a new generation of queens which will completely vacate the nest and find a sheltered spot to over-winter before establishing a new nest the following season.

In this section we take a look at the different types of bee that go to make up the colony.

TYPES

There are 2 sexes of honey bee. There are the 2 castes of female bee – the queen and the worker – and the male drone. Each has an essential role to play in the life of the colony and the annual cycle the colony goes through.

THE QUEEN

The queen honey bee is effectively the “mother” of the colony. Her main role is to lay eggs and lots of them. If there are enough cells available she will lay up to 2500 a day. Once she has laid an egg, she has no further role to play in the care or upbringing of the larva that emerges from the egg.

Under normal circumstances, the queen is the only egg laying bee in the colony. This ultimately makes her the mother to the colony. Each emerging young bee is her genetic descendant (and that of the multiple drones she has previously mated with).

The regal title given to this caste causes a perception of the queen being the “boss”. She may be the largest bee in the colony and have her every need attended to however she is very much a servant of the colony and her actions are very much determined by the workers in the colony.

Queen life cycle

A queen starts out as a simple fertilised egg. At this stage there is no difference between her and any other worker. Whether or not an egg becomes a queen is down to the workers in the colony. If the colony is ready to swarm or detects that it has a failing queen or even no queen the “house” worker bees will alter how they feed one or more larvae that hatch out.

If the colony has time to prepare to raise new queens, it will extend one or more existing worker cells in the honey comb to form “queen cups”. These will usually be towards the bottom or edge of the main brood area of the comb. The queen lays an egg in these queen cups and once hatched (3 -3½ days from being laid) the new larva is fed a rich diet of “royal jelly” by the “nurse” bees. This rich food allows the larvae to grow larger and more quickly than a normal worker. The new queen (known as the “virgin queen”) emerges 16 days after the eggs was laid. This compares to the 21 days taken by a worker bee or 24 by the drone.

If a queen is lost for whatever reason (e.g. is killed accidentally by the beekeeper), the colony will resort to making emergency queen cells. Providing there are eggs or very young larvae (up to 3 days old) present the colony will use these to raise several new queens.

They will draw out existing cells and start feeding what would have been ordinary worker larvae with royal jelly.

The rich diet fed to the developing queen larva alters the anatomy of the larva (from that of the worker). The abdomen becomes notably longer than that of her sister workers. The larger abdomen accommodates the enlarged reproductive organs, namely the ovaries and spermatheca.

When the virgin queen emerges from her cell, one of 4 fates await her.

- She will be attacked and possibly killed by another queen that emerged ahead of her

- She will seek out and find other emerging queens and kill them (sometimes by stinging through the cell capping before the virgin queen has emerged)

- She will be ushered out of the colony to fly off with a number of other bees from the colony (a swarm), or

- She will be accepted by the colony, the workers of which will immediately start to care for her.

The virgin queen will typically stay within the colony for a few days in order to feed and gain strength and allow her reproductive organs to mature a little further. Following this initial “rest period”, the virgin queen will emerge from the colony and make a few reconnaissance flights. She probably does this to ensure she knows where the hive is and also to find where drones congregate. The queen is particularly vulnerable to being taken by birds when flying due to her size and it makes sense for her to avoid lengthy flights. When ready, usually any time up to around 21 days from emerging from her cell, the queen will make a “mating flight”. She will head straight for the drone congregation site usually in the vicinity of the queen’s colony and up to 30 metres from the ground. The queen flies up to the drones and mates repeatedly with several of them. Once her spermatheca is full, she heads back to the colony.

She relies on the attendant workers for her every need. They feed and groom her and remove her wastes. The queen will spend the next season or two laying eggs. The number she lays will largely depend on the activities of the colony. They will control how many cells remain vacant for egg laying (increasing and decreasing the amount of stores of pollen and honey according to seasonal variations) and will control her egg production by varying the amount of food she is fed.

The queen produces a pheromone called queen mandibular pheromone (also known as “queen substance”). As the workers clean her they distribute queen substance around the colony. This serves to maintain the colony in a “normal” state. However, as the queen gets older and begins to wear out, typically coinciding with a steady reduction in the number of eggs laid, she produces less and less queen substance. The colony senses this and begins preparation for her ultimate removal. This occurs by a process of supercedure where a new queen is raised and the old is killed off either by the workers or the new queen. Supercedure is a natural process that will face nearly every queen. Supercedure may occur within the colony or once a colony has swarmed. A prime swarm (the first to leave a colony) will have the incumbent queen. Once the swarm establishes its new home, a new queen is raised and the old queen is killed.

Workers

The worker bee is – as the name suggests – the power house behind the colony. Workers are all female. They carry out almost all the duties that go into building and maintaining a colony.

They are the smallest bee within the colony, being smaller than either the drone or queen.

Worker bees, like the queen, possess a sting. The sting is a modified ovipositor or egg laying tube. Despite the presence of reproductive organs, the workers are infertile and lack the reproductive capacity of the queen. Nevertheless, workers can lay eggs under certain circumstances – usually in the total absence of a queen (pheromones produced by the queen inhibit egg laying by the workers). However, due to being infertile the eggs develop into drones.

There are however some sub-species of honey bee (e.g. the “Cape Bee” of South Africa) where workers can lay eggs resulting in worker brood (see Bee Species).

Life Cycle

The worker bee starts out as a normal egg laid by the queen. The eggs hatches around 3 – 3 ½ days from being laid. The larva is fed “brood food” or “bee milk” which is largely a combination of nectar (or dilute honey), pollen and enzymes from the saliva of the “nurse” bees. The pollen provides the necessary protein required for rapid growth and the sugar the energy source. It is likely that the enzymes break down some of the more complex carbohydrates and proteins into simpler molecules that can be consumed by the larvae.

A worker larva is fed approximately half the quantity of brood food fed to a queen larva. However, there is little difference in the ingredients of the food that is fed to each. Instead, it is more to do with the relative proportions of those ingredients. Research suggests that the queen larva is fed a significantly higher proportion of sugar in its food (royal jelly) and that this extra energy boost – given to a larva within its first 3 days – promotes an increase in certain growth hormones that cause what would otherwise become a worker to become a queen.

Following its emergence from the egg, the larva becomes a pupa after around 10 days and emerges from the cell as a young bee 21 days after the egg was first laid.

Division of Labour

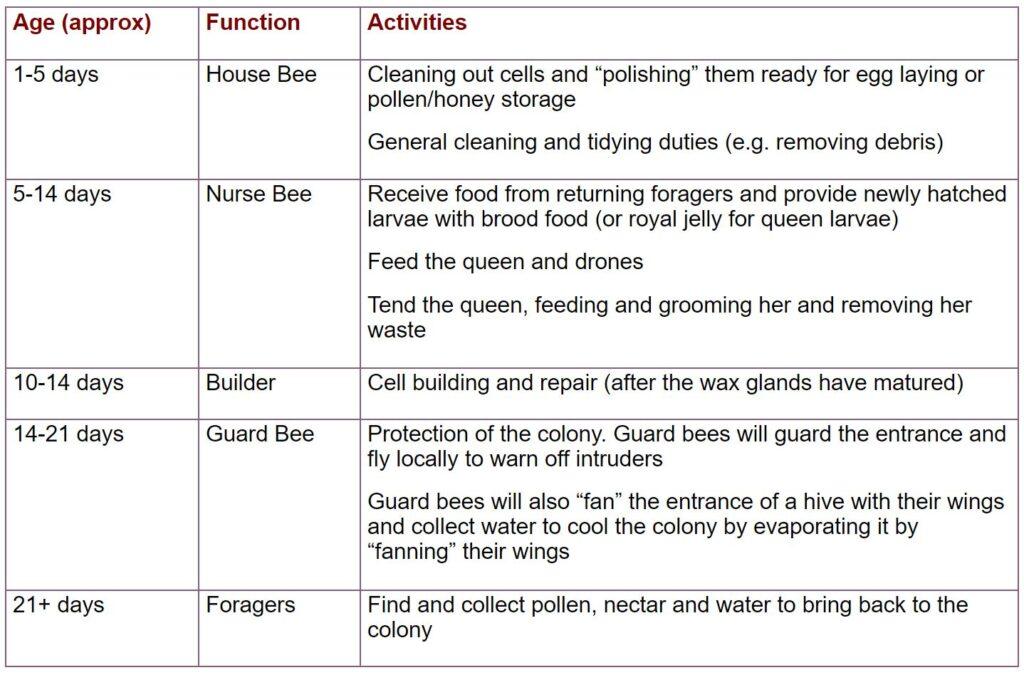

Worker bees seem to follow a pattern of promotion within their society. As each worker gets older it progresses to new duties. It should be noted that bees can revert back to previous jobs or progress more quickly through the jobs depending on the needs of the colony. These are:

DRONES

Drone bees are the hapless males within a colony. They seemingly have little or no purpose within the colony: they take no part in hive building or maintenance; they don’t defend the colony (drones do not possess a sting); they don’t gather food or nurture the larvae.

However, drones perform one vital role in that they are responsible for genetic variation within successive generations of bees. Their primary purpose is to mate with virgin queens, spreading their genes to different colonies. Without this function, honey bee populations would quickly fall victim to disease and probably become extinct. Genetic variation allows living things to stay one step ahead of the disease causing organisms.

Drone bees are larger than workers, but normally smaller than the queen. They are characterised by their large compound eyes, which appear to come together at the top, and rounded stocky bodies. They are a result of unfertilised eggs which may be laid by a queen or worker. Drones are classified as being “haploid” in that they only posses one half of the pairs of genes found in the “diploid” workers and queen.

Life Cycle

Normally, drone eggs are laid only by the queen. The queen hold the eggs and sperm separately and has the choice as to whether or not an egg is fertilised as it is laid. The queen will lay drone eggs in drone cells. These are cells which have been enlarged by the workers in order to accommodate the larger body size of the drone. The queen detects the difference in cell type and lays worker or drone eggs accordingly.

As with the two female castes, drone eggs hatch on day 3 – 3 ½. The larva is fed brood food and allowed to develop until the cell is capped over on day 10. The larva spins a cocoon within the cell and undergoes metamorphosis turning into a pupa. The drone emerges as a young adult on day 24.

The young drone, being unable to gather food for itself, is fed by the house workers. After a few days, the drone will begin to carry out reconnaissance flights. Their ability to navigate is probably the best of all 3 castes as they typically have around 75-80% more facets to their compound eyes than the workers or queen allowing them to build a better visual map of the immediate area. Around 2 weeks after the drone emerges from the cell it will be mature enough to mate.

Drone bees typically come together to fly in certain areas known as “drone congregation areas” or “mating yards”.

A wasp enjoys a pupa meal.

These areas are often several metres from the ground (up to 30 m) and will typically be in the vicinity of the apiary from where they have come however drones can fly several miles to find other established congregation areas. No one really knows how drones find congregation areas that may be a few miles away. It is likely that they are able to sense the odours of other drones over some distance using their enlarged and highly sensitive antennae. A congregation area may have from several hundred to several thousand drones.

A virgin queen will have already found such a congregation area from early reconnaissance flights. On her mating flight the queen will head straight for the congregation area. The drones will sense her arrival (their notably large antennae have 10 times the number of sensory receptors as those of workers or queens) and will immediately start to chase after her.

Several drones will mate with the queen. Each drone mounts the queen in turn and inserts his endophallus into the queen. The drone’s sex organs inflate (almost explosively) within the queen, pumping sperm into her. This rapid inflation and expulsion of sperm causes him to spring backwards and fall away from the queen. The endophallus is gripped by the opening of the queen’s oviduct and results in the drone’s endophallus and part of the drone’s hind gut being ripped out of his abdomen. Each additional drone will remove from the queen the endophallus of his predecessor before undergoing the same fate. After mating the drone will often fall to the ground where he will die.

Drones will be reared all through the season. For those that haven’t mated, they will be forcibly ejected from the colony by the workers at the end of the season (late summer/early autumn) as they will be of no benefit during the winter. After ejection they soon starve or die from cold.

Photos Copyright Richard Senior