It is a simple fact that honey bees can sting. They don’t go out of their way to sting. They don’t intend to harass us and cause pain at the first opportunity. Honey bees sting usually in a selfless act of defence of their colony and occasionally as a self defence mechanism because they have been physically trapped or caught up in some way. In fact, bees will tend to “angrily” buzz around anyone or anything that comes too close to the colony and will resort to stinging as a last resort.

Animals in the wild have become so wary of bees over the millennia that “buzzing” is often enough to send them scampering away. In parts of Africa where people and elephants come into conflict with elephants that destroy crops, scientists have found that by placing loud speakers – triggered by sensors – in strategic places, they can send elephants running for cover by playing the sound of a swarm of angry bees. The buzzing of bees has a similar affect on many people.

THE BEE STING

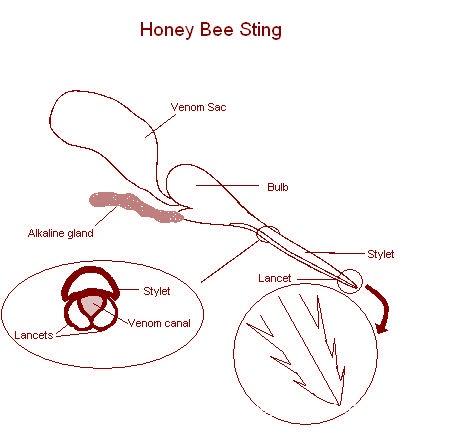

The stinging apparatus of the honey bee is in fact a modified ovipositor (egg laying tube) that all bees and wasps have. In some bees and wasps the ovipositor is nothing more than a simple egg-laying tube designed to get eggs into hard to reach nooks, whilst in others it is stiffened to allow holes to be made in wood or penetrate the bodies of other insects in order to lay eggs. As the “stinger” is a modified egg laying tube, it goes without saying that only the female bees posses a sting.

In honey bees, the ovipositor is formed into a rigid shaft. The shaft is formed from the “stylet” and two “lancets”. The inner space within the shaft is the venom or poison canal used to deliver the bee venom into the victim.

During the process of stinging the bee contracts muscles in its abdomen that cause the shaft of the sting to protrude from the tip of the abdomen. The bee arches the tip of its abdomen down pushing the tip of the shaft into the victim.

The lancets have backward pointing barbs which grip the skin. The lancets move back and forth in opposite directions to each other which act to drive the sting further into the victim.

During the stinging process muscles around the alkaline gland and venom sac contract to squeeze their contents into the bulb. The ends of the lancets that sit within the bulb draw venom into the venom canal as they reciprocate back and forth.

Honey bees can often repeatedly sting other insects. However after stinging a mammal, when the bee pulls away or is knocked off by the victim the barbs cause the sting to remain in the skin along with the rest of the stinging apparatus and part of the hind gut of the bee. Even when the bee has gone, the muscles of the sting apparatus are able to keep pumping venom through the venom canal.

DEALING WITH A STING

Once stung there is little that can be done to avoid the effects of the venom – much of the venom will have been injected in the first few seconds after being stung. However, once the bee has pulled away or been knocked off the sting will continue to pump venom into the skin for anything up to 2 minutes. Therefore, it is recommended that the sting is removed as quickly as possible.

There is some debate as to whether the sting should be scraped off the skin or removed by any means – including pulling it out by pinching it between thumb and finger. Most believe that it should be scraped off (with a hive tool or finger nail) to avoid squeezing more venom into the skin. Squeezing the venom sac should probably be avoided if possible however removing the sting quickly (even by picking it out) will reduce the amount of venom injected.

BEE VENOM

It’s main target of a bee’s sting is other insects. However, bee venom is also effective against larger animals like ourselves causing enough discomfort to make us leave the bees alone. A typical worker bee carries around 100 to 150 micrograms of venom in its venom sac and delivers up to 50 micrograms in one sting (depending on how quickly you can remove the sting). This is a tiny amount (despite the pain) and it is reckoned that it would take close to 1000 stings to kill an average, non-allergic, healthy adult human (maybe 500 for a small child). Not that this should make us complacent, because 200+ stings could lead to very serious health complications.

Bee venom is poisonous. It is composed of a complex mixture of substances, the main active ingredients being:

– Mellitin: A toxic peptide with a highly destructive effect on cells

– Apimin: A toxic peptide that damages nerve cells

– MCD: Mast Cell Degranulating peptide causes histamine to be released from mast cells with the skin

– Hyaluronidase: An enzyme that breaks down hyaluronic acid, an agent which helps bind cells together

– Phospholipase A: An enzyme which breaks down cell walls rupturing them

Other substances are present in smaller amounts and these include histamine, dopamine and noradrenaline.

The combine effect of these constituents is to rupture and kills affected cells, open up tissue and spread the effects of the venom. The toxic effects cause pain, the damage causes swelling and the body’s reaction later causes itching.

REACTION TO STINGS

The reaction to a bee sting is normally (in non-allergic and non-immune individuals) very localised and typically very minor. Immediately following a sting there will be an intense (acute) feeling of pain. A red mark will develop at the site of the sting and the immediate area (1 to 2cm across) may become pale and swollen (a weal). This is followed by a red patch around the sting site (2 to 10cm across) and the area may become swollen. The degree of swelling largely depends on where the sting has occurred – softer skin swelling more than tougher skin. It is especially important that we avoid being stung on the eyeball or in the mouth. A sting in the mouth could easily swell to block the airways and a sting to the eye could lead to permanent damage to the eye, even a loss of sight.

Anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours later the pain will subside and swelling go down.

Probably the best way to relieve the immediate effects of a sting is to apply some ice simply to reduce the pain and swelling. There are numerous alternative remedies that are used, including bicarbonate of soda (to neutralise the acidity of bee venom), however these are typically not based on scientific fact and some may do more harm than good. Ice will act more quickly. If itching develops later, an antihistamine can be taken or a hydrocortisone cream applied (it it not recommended that antihistamine creams are used as these can result in skin sensitivity rash in some).

ALLERGY

The reaction of a person who is allergic to bee venom can be drastically different to the basic reaction described above. There is no one degree of allergic response, with allergic individuals experiencing anything from mild discomfort to possible death. Some may exhibit the development of allergy and then see their reaction subside and eventually disappear; some may never progress beyond mild systemic reactions, whilst other may develop anaphylaxis.

Immunity

We would normally expect our bodies to react to the invasion of foreign bodies and get rid of them. The large molecules of peptides and enzymes in bee venom are just such foreign bodies (antigens). On detection of these antigens, we produce antibodies which neutralise them allowing them to be removed and ultimately ejected from the body. On subsequent contact with bee venom, our body will have hopefully learnt the makeup of the foreign bodies and will produce highly specific antibodies which “mop up” the bee venom very quickly. This antibody is known as Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and accounts around 80% of all our antibodies. A person who develops immunity to bee venom is one who successfully builds up the ability to produce increasing amounts of bee venom specific IgG. The most immune beekeepers will barely notice the odd bee sting – just experiencing a short period of pain and a small red dot.

Allergic reactions

Those who develop allergy are, unfortunately, genetically predisposed to do so. The reasons why are complex. It does not necessarily follow that a normally allergic individual (e.g. one who is allergic to pollen, dust might, animal hair, etc) will develop bee venom allergy. It’s the “luck of the draw”. An allergic person who is stung will produce antibodies in response to the foreign bodies. Only this time, they will produce a different antibody known as Immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE normally acccounts for much less than 1% of our antibodies and it is quite normal for it to exist in us. However, in allergic individuals, there is a tendency to produce excess amounts of bee venom-specific IgE. The latter binds to the surface of white blood cells known as basophils and mast cells and form receptor sites specific to bee venom. Following a new sting, the components of the venom bridge the receptors formed by IgE causing the white cells to release histamine and other allergy substances. As a rule, the more bee venom-specific IgE a person produces, the greater the allergic response.

An allergic person (or one who is predisposed to become allergic if stung) will typically have no worse a reaction than anyone else upon being stung for the first time. The next few stings however, may result in a worsening of the reactions. The degree of swelling is likely to increase from one sting to the next. Instead of swelling extending up to 5 or 10 centimetres across, it may affect much of a limb. After further stings, a person might notice that they get itching elsewhere on the body (urticaria or hives) including around the mouth and eyes. They might become wheezy, feel dizzy or even sick. These are all symptoms of developing bee venom allergy and medical advice should be sought.

If the allergy is left untreated it could lead to full anaphylaxis. This is where the reaction becomes extreme and life threatening.

Anaphylactic shock is an immediate, life threatening allergic response to bee venom (or whichever “allergen” the person reacts to). It is caused by the body’s production of excessive amounts of histamine which causes blood vessels to dilate throughout the body – causing the blood pressure to drop dramatically. Other substances released with histamine cause constriction of the airways. The reaction can lead to a loss of consciousness and a collapse of the blood circulation leading to death.

The main symptoms of an anaphylactic shock may include

- – Severe difficulty in breathing

- – Swelling to the eyes, mouth or throat

- – General swelling (or swelling to parts of the body away from the sting area)

- – Feeling faint

- – Nausea

- – Stomach pain

- – A feeling of “doom”

- – Unconsciousness

If, after being stung, anyone develops any immediate and severe symptoms such as difficulty in breathing, weakness, faintness, stomach pain, etc, they should call (an ambulance or alert someone else to do so) straight away.

This level of severity is extremely rare. There are no statistic available to tell us how many people die from bee venom allergy each year. However, approximately 5 people die each year in the UK from insect stings (including wasps). The vast majority of people who develop anaphylaxis will live to tell the tale.

Tips:

- When going out to do any beekeeping, tell someone where you are going and when you expect to return.

- Take a mobile phone (and a note of exactly where your apiary is), you will usually have enough time to call an ambulance. Even if you can’t speak, providing you dial 999 the emergency services can locate where your mobile is.

- If, following a sting, you feel unwell, move away from the hives as quickly as possible. If possible enter a building or car (any bees on you should fly off you toward the light). Dial 999.

- If you have previously had a systemic reaction following a sting (e.g. large amount of swelling to the sting area, swelling elsewhere, tight chest, wheezing, sickness or faintness), consider taking an antihistamine tablet 1 to 2 hours before you go to the bees. You need to bear in mind that some antihistamines can make your drowsy and may affect your driving and if you are taking any other medication you will need to seek medical advice to check it is ok to take the antihistamine. If in doubt about the severity of any reaction you might have, seek medical advice.